14/02/2022

Kétamine: Stable longtemps quand il fait très chaud

Ketamine Stability over Six Months of Exposure to Moderate and High Temperature Environments

Foertsch MJ et Al. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021 Jun 21;1-6.

Background:

All medications should be stored within temperature ranges defined by manufacturers, but logistical and operational challenges of prehospital and military settings complicate adherence to these recommendations. Lorazepam and succinylcholine experience clinically relevant heat-related degradation, whereas midazolam does not. Because ketamine's stability when stored outside manufacturer recommendations is unknown, we evaluated the heat-related degradation of ketamine exposed to several temperature ranges.

Methods: One hundred twenty vials of ketamine (50 mg/mL labeled concentration) from the same manufacturer lot were equally distributed and stored for six months in five environments: an active EMS unit in southwest Ohio (May-October 2019); heat chamber at constant 120 °F (C1); heat chamber fluctuating over 24 hours from 86 °F-120 °F (C2); heat chamber fluctuating over 24 hours from 40 °F-120 °F (C3); heat chamber kept at constant 70 °F (manufacturer recommended room temperature, C4). Four ketamine vials were removed every 30 days from each environment and sent to an FDA-accredited commercial lab for high performance liquid chromatography testing. Data loggers and thermistors allowed temperature recording every minute for all environments. Cumulative heat exposure was quantified by mean kinetic temperature (MKT), which accounts for additional heat-stress over time caused by temperature fluctuations and is a superior measure than simple ambient temperature. MKT was calculated for each environment at the time of ketamine removal. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the concentration changes at each time point.

Results: The MKT ranged from 73.6 °F-80.7 °F in the active EMS unit and stayed constant for each chamber (C1 MKT: 120 °F, C2 MKT: 107.3 °F, C3 MKT: 96.5 °F, C4 MKT: 70 °F). No significant absolute ketamine degradation, or trends in degradation, occurred in any environment at any time point. The lowest median concentration occurred in the EMS-stored samples removed after 6 months [48.2 mg/mL (47.75, 48.35)], or 96.4% relative strength to labeled concentration.

Conclusion: Ketamine samples exhibited limited degradation after 6 months of exposure to real world and simulated extreme high temperature environments exceeding manufacturer recommendations. Future studies are necessary to evaluate ketamine stability beyond 6 months.

| Tags : kétamine

09/02/2022

Efficacité et sécurité de la kétamine pour l'analgésie préhospitalière du blessé de guerre

07/12/2021

Kétamine préhospitalière: Reco US

| Tags : kétamine

22/06/2021

RSI: Que fait on ?

Rapid sequence induction: An international survey

Klucka J et Al. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020 Jun;37(6):435-442

-----------------------------------

La kétamine, la kétamine la kétamine, la kéta......, la............ Mais pour vous ouvrir l'esprit lisez donc également cet article

-----------------------------------

Background: Rapid sequence induction (RSI) is a standard procedure, which should be implemented in all patients with a risk of aspiration/regurgitation during anaesthesia induction.

Objective: The primary aim was to evaluate clinical practice in RSI, both in adult and paediatric populations.

Design: Online survey.

Settings: A total of 56 countries.

Participants: Members of the European Society of Anaesthesiology.

Main outcome measures: The aim was to identify and describe the actual clinical practice of RSI related to general anaesthesia.

Results: From the 1921 respondents, 76.5% (n=1469) were qualified anaesthesiologists. When anaesthetising adults, the majority (61.7%, n=1081) of the respondents preoxygenated patients with 100% O2 for 3 min and 65.9% (n=1155) administered opioids during RSI.

The Sellick manoeuvre was used by 38.5% (n=675) and was not used by 37.4% (n=656) of respondents. First-line medications for a haemodynamically stable adult patient were propofol (90.6%, n=1571) and suxamethonium (56.0%, n=932). Manual ventilation (inspiratory pressure <12 cmH2O) was used in 35.5% (n=622) of respondents. In the majority of paediatric patients, 3 min of preoxygenation (56.6%, n=817) and opioids (54.9%, n=797) were administered. The Sellick manoeuvre and manual ventilation (inspiratory pressure <12 cmH2O) in children were used by 23.5% (n=340) and 35.9% (n=517) of respondents, respectively. First-line induction drugs for a haemodynamically stable child were propofol (82.8%, n=1153) and rocuronium (54.7%, n=741).

Conclusion: We found significant heterogeneity in the daily clinical practice of RSI. For patient safety, our findings emphasise the need for international RSI guidelines

| Tags : intubation, kétamine

28/11/2020

Kétamine: Recommendations de l'ACEP

| Tags : kétamine

15/01/2017

ISR: Plutôt kétamine ?

Significant modification of traditional rapid sequence induction improves safety and effectiveness of pre-hospital trauma anaesthesia.

Lyon RM et Al. Crit Care. 2015 Apr 1;19:134

-------------------------------------------

Faut-il utiliser la kétamine ou l'étomidate ? Le travail présenté milite pour l'emploi de la kétamine, mais ceci reste controversé (voir également ici)). C'est aussi le choix présenté dans la procédure du sauvetage au combat, du fait de la polyvalence d'emploi de la kétamine tant dans ses indications que de ses voies d'administration. On rappelle quand même que si l'ISR facilite grandement les conditions de l'intubation oro-trachéale en médecine préhospitalière métropolitaine, nos conditions spécifiques d'exercice ne correspondent pas à cette dernière. Avant de réaliser une telle induction, encore faut-il être valider l'indication de l'intubation au milieu de nulle part. Par ailleurs la réalisation de ce geste sous anesthésie locale doit également être envisagée. Ceci est conforme aux recommandations sur le sujet.

-------------------------------------------

INTRODUCTION:

Rapid Sequence Induction of anaesthesia (RSI) is the recommended method to facilitate emergency tracheal intubation in trauma patients. In emergency situations, a simple and standardised RSI protocol may improve the safety and effectiveness of the procedure. A crucial component of developing a standardised protocol is the selection of induction agents. The aim of this study is to compare the safety and effectiveness of a traditional RSI protocol using etomidate and suxamethonium with a modified RSI protocol using fentanyl, ketamine and rocuronium.

METHODS:

We performed a comparative cohort study of major trauma patients undergoing pre-hospital RSI by a physician-led Helicopter Emergency Medical Service. Group 1 underwent RSI using etomidate and suxamethonium and Group 2 underwent RSI using fentanyl, ketamine and rocuronium. Apart from the induction agents, the RSI protocol was identical in both groups. Outcomes measured included laryngoscopy view, intubation success, haemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation, and mortality.

RESULTS:

Compared to Group 1 (n = 116), Group 2 RSI (n = 145) produced significantly better laryngoscopy views (p = 0.013) and resulted in significantly higher first-pass intubation success (95% versus 100%; p = 0.007). A hypertensive response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation was less frequent following Group 2 RSI (79% versus 37%; p < 0.0001). A hypotensive response was uncommon in both groups (1% versus 6%; p = 0.05). Only one patient in each group developed true hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg) on induction.

CONCLUSIONS:

In a comparative, cohort study, pre-hospital RSI using fentanyl, ketamine and rocuronium produced superior intubating conditions and a more favourable haemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation. An RSI protocol using fixed ratios of these agents delivers effective pre-hospital trauma anaesthesia.

12/03/2016

Douleur: Pendant l'évacuation, Kétamine = Morphine ?

Prehospital Pain Medication Use by U.S. Forces in Afghanistan

Shackelford SA et Al. Mil Med. 2015 Mar;180(3):304-9

We report the results of a process improvement initiative to examine the current use and safety of prehospital pain medications by U.S. Forces in Afghanistan. Prehospital pain medication data were prospectively collected on 309 casualties evacuated from point of injury (POI) to surgical hospitals from October 2012 to March 2013. Vital signs obtained from POI and flight medics and on arrival to surgical hospitals were compared using one-way analysis of variance test. 119 casualties (39%) received pain medication during POI care and 283 (92%) received pain medication during tactical evacuation (TACEVAC). Morphine and oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate were the most commonly used pain medications during POI care, whereas ketamine and fentanyl predominated during TACEVAC.

Ketamine was associated with increase in systolic blood pressure compared to morphine (+7 ± 17 versus −3 ± 14 mm Hg, p = 0.04). There was no difference in vital signs on arrival to the hospital between casualties who received no pain medication, morphine, fentanyl, or ketamine during TACEVAC. In this convenience sample, fentanyl and ketamine were as safe as morphine for prehospital use within the dose ranges administered. Future efforts to improve battlefield pain control should focus on improved delivery of pain control at POI and the role of combination therapies.

| Tags : kétamine

Douleur: Kétamine d'abord ?

Prehospital and En Route Analgesic Use in the Combat Setting: A Prospectively Designed, Multicenter, Observational Study

Lawrence N. Petz LN et Al. , Mil Med. 2015 Mar;180(3 Suppl):14-8

Background:

Combat injuries result in acute, severe pain. Early use of analgesia after injury is known to be beneficial. Studies on prehospital analgesia in combat are limited and no prospectively designed study has reported the use of analgesics in the prehospital and en route care setting. Our objective was to describe the current use of prehospital analgesia in the combat setting.

Methods:

This prospectively designed, multicenter, observational, prehospital combat study was undertaken at medical treatment facilities (MTF) in Afghanistan between October 2012 and September 2013. It formed part of a larger study aimed at describing the use of lifesaving interventions in combat. On arrival at the MTF, trained on-site investigators enrolled eligible patients and completed standardized data capture forms, which included the name, dose, and route of administration of all prehospital analgesics, and the type of provider who administered the drug. Physiological data were retrospectively ascribed as soon as practicable. The study was prospectively approved by the Brooke Army Medical Center institutional review board.

Results:

Data were collected on 228 patients, with 305 analgesia administrations recorded. The predominant mechanism of injury was blast (50%), followed by penetrating (41%), and blunt (9%). The most common analgesic used was ketamine, followed by morphine.

A combination of analgesics was given to 29% of patients; the most common combination was ketamine and morphine. Intravenous delivery was the most commonly used route (55%). Patients transported by the UK Medical Emergency Response Team (MERT) or U.S. Air Medical Evacuation (Dust-off) team were more likely to receive ketamine than those evacuated by U.S. Pararescue Jumpers (Pedro). Patients transported by Medical Emergency Response Team or Pedro were more likely to receive more than 1 drug. Patients who received only ketamine had a higher pulse rate ( p < 0.005) and lower systolic blood pressure ( p = 0.01) than other groups, and patients that received hydromorphone had a lower respiratory rate ( p = 0.04).

Conclusions: In our prospectively designed, multicenter, observational, prehospital combat study, ketamine was the most commonly used analgesic drug. The most frequently observed combination of drugs was ketamine and morphine. The intravenous route was used for 55% of drug administrations.

| Tags : kétamine

03/01/2016

Kétamine: Prudence quand même

Is ketamine ready to be used clinically for the treatment of depression ?

Colleen L. Med J Aust 2015 Dec 14;203(11):425.

A single dose of ketamine produces rapid antidepressant effects, but attaining lasting remission remains a challenge

Il existe un engouement très important pour l'emploi de kétamine pour la prise en charge de la dépression (1,2). Pour autant il ne faut pas oublier les effets secondaires de cette dernière lorsqu'elle est administrée de manière chronique. De nombreuses données issues de l'emploi récréatif de la kétamine mettent en avant de nombreux effets secondaires comme l'hépatotoxicité, les dysfonctions vésicales et, possiblement des troubles cognitifs. Même si aucun effets de ce type n'est retrouvé lors d'emploi encadré médicalement, la prudence reste de mise.

01/01/2016

Kétamine et dépression: Raz de marée

Anesthesiologists Take Lead As Ketamine Clinics Proliferate

A growing number of anesthesiologists are opening private clinics that provide off-label infusions of ketamine to patients suffering from treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, suicidality and other disorders. Psychiatrists and other physicians have also recently opened clinics.

The cost per infusion ranges from $400 to $1700, with most clinics charging about $500. Patients pay out-of-pocket since most health insurance plans do not cover the off-label procedure.

Despite the cost, patients seek the treatments after their antidepressants and other therapies prove ineffective. Proponents claim that, when administered as an IV infusion in a subanesthetic dose (typically 0.5 mg/kg body weight) over 40 to 45 minutes, ketamine begins reversing symptoms of depression for two of three patients in less than 24 hours, with effects persisting for a week or more. Nearly three of four patients suffering from suicidality experience an almost immediate reversal in thinking.

“The results are amazing,” said anesthesiologist Glen Z. Brooks, MD, founder and medical director of New York Ketamine Infusions LLC, in New York City, and one of the pioneers in the field. His success rate averages about 65% when measured by standardized mood and function surveys, and is even greater for younger adults, he said. The typical course of treatment is six infusions administered every other day for two weeks followed by “maintenance” or “booster” infusions as needed, typically every six weeks afterward.

“The procedure is very well tolerated. We have seen no complications during or after the 45-minute infusions in now close to 8,000 treatments,” Dr. Brooks told Anesthesiology News. “I have been treating some patients for as long as three years with ongoing remission of their symptoms, so efficacy can be very long term.”

Ketamine Can Work Quickly

Ketamine was synthesized in the early 1960s and approved for human anesthesia a decade later. It has been administered to millions of patients worldwide, and continues to be an anesthetic of choice for pediatric patients who may experience adverse reactions to other agents. It also is used in pain clinics and when changing dressings of severe burn victims.

For treating depression, it only takes two ketamine infusions to determine whether a patient will respond favorably, whereas traditional antidepressants can take four to six weeks and will work about 30% of the time. During the ketamine infusion, patients remain awake or in a twilight state. Dizziness or a sensation of dissociation is common, and generally disappears shortly after the infusion. “We notice a 50% improvement in depression scores within the first three infusions, which take six days,” said anesthesiologist Enrique Abreu, MD, medical director at Portland Ketamine Clinic in Oregon. “Overall, 75% to 80% of patients see improvement in depression, mood and anxiety after six treatments,” he told Anesthesiology News.

Some experts in depression research have called ketamine’s “rapid and robust” antidepressant properties “arguably the most important discovery in half a century” (Science 2012;338:68-72). Others urge caution, citing concerns over long-term side effects and potential for abuse. The latter concern stems from ketamine being an illicit “rave” drug (nicknamed “Special K” or “Vitamin K”) that creates intense, short-term hallucinations, dissociation and psychotomimetic effects. Ketamine also is pharmacologically similar to PCP (phencyclidine), a powerful psychotomimetic drug.

While the World Health Organization has long included ketamine on its model list of essential medicines for anesthesia, the drug also has been placed under national control in more than 60 countries, especially in Asia, where abuse is common. Bladder problems and cognitive declines have been observed in long-term recreational ketamine abusers, but none of these effects has been observed in clinical trials.

The anesthesiologists and psychiatrists who administer ketamine infusions for severe depression report overwhelmingly positive outcomes. New Jersey psychiatrist Steven Levine, MD, decided to explore ketamine after reading reports of clinical studies conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). “The results were unlike anything we had seen before, with positive outcomes emerging within days or weeks,” Dr. Levine said. “Some really sick people were getting significantly better within hours. I couldn’t convince myself to not do it.”

Dr. Levine quizzed several anesthesiologist friends about potential dangers before opening his clinic. “They were totally nonplussed about the low dosage used in the infusion, unconcerned about any potential for bad side effects,” Dr. Levine told Anesthesiology News. “They were used to giving it in much higher doses for anesthesia and even higher doses in burn units when changing dressings.” Dr. Levine opened Ketamine Treatment Centers of Princeton LLC, in New Jersey, in 2011 and has since treated about 500 patients. He plans to open clinics in Baltimore, Florida and Denver in early 2016.

Mechanisms of Action

Typical FDA-approved antidepressants target neurons that inhibit the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. Ketamine works more broadly by blocking the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, a component of the fast-signaling glutamate system that affects nearly all neurons. Brain scans reveal that ketamine rapidly induces synaptogenesis, repairing damage caused by chronic stress.

Many clinical trials of ketamine for depression have been, and continue to be, conducted at NIMH. A seminal study published in 2006 was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover trial led by Carlos A. Zarate Jr., MD, chief of NIMH’s neurobiology and mood disorders treatment section. In this year-long study, patients receiving ketamine showed significant improvement in depression compared with placebo after 24 hours, with effects remaining “moderate to large” after one week (Arch Gen Psych 2006;63:856-864). “This line of research holds considerable promise for developing new treatments for depression with the potential to alleviate much of the morbidity and mortality associated with the delayed onset of action of traditional antidepressants,” Dr. Zarate and colleagues wrote, citing the need to improve the drug’s long-term effectiveness.

Since then, studies at NIMH and elsewhere have demonstrated ketamine’s efficacy for rapidly diminishing suicidal ideation (Drugs R D 2015;15:37-43), unipolar and bipolar depression (Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;23:CD011612; Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;29:CD-011611), and for PTSD and other anxiety disorders (JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:681-688).

The American Psychiatric Association’s Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments urges caution when it comes to clinical use of ketamine. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of ketamine and other NMDA receptor antagonists (Am J Psych 2015;172:950-966), the task force concluded: “The antidepressant efficacy of ketamine … holds promise for future glutamate-modulating strategies.” However, the “fleeting nature of ketamine’s therapeutic benefit, coupled with its potential for abuse and neurotoxicity, suggest that its use in the clinical setting warrants caution.”

When asked to comment on anesthesiologists performing off-label ketamine infusions, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) provided this statement to Anesthesiology News: “The American Society of Anesthesiologists is committed to promoting the highest standards of care for the patients they serve. This new practice area has been brought to ASA’s attention and will be carefully reviewed.”

Gaining Legitimacy

According to ketamine advocate Dennis Hartman, at least 60 private clinics in the United States offer off-label infusions, and the number is growing. The former business executive says ketamine infusions rescued him from suicide in 2012, and ongoing treatments have brought his depression into remission. As founder and CEO of the nonprofit Ketamine Advocacy Network, Mr. Hartman now works full time with practitioners and patients to help gain legitimacy for the field. His website lists 18 ketamine practitioners in the United States, most of them anesthesiologists, with a smaller number of psychiatrists and neurologists, plus one emergency medicine physician and one family physician.

“There are others that we have not vetted and others that we’ve purposefully chosen not to include,” Mr. Hartman explained, most often because they charge too much money or require expensive additional tests or medical procedures for which clinical evidence is lacking. “There are still others who offer the treatment but want to be under the radar,” Mr. Hartman told Anesthesiology News.

Anesthesiologists generally believe they are uniquely qualified to administer ketamine infusions because of their expertise with anesthetics. “I want this to stay as something for anesthesiologists,” said Steven Mandel, MD, founder of Ketamine Clinics of Los Angeles. “Nevertheless, I don’t want there to be a conflict between anesthesiology and psychiatry, because ketamine definitely needs an anesthesiologist to administer it and definitely needs a psychiatrist or psychologist involved because they know about psychopathology,” he said. But ketamine does take “considerable vigilance and finesse” to infuse properly, he added, even for those with years of operating room experience. “This is different because the ‘sweet spot’ for treatment is this side of unconsciousness in the moderate- to deep-sedation range,” Dr. Mandel explained.

Many psychiatrists, on the other hand, believe they are best suited to oversee ketamine therapy because of their expertise in treating patients with depression, PTSD and other conditions. In those ketamine clinics run by psychiatrists, the IV insertion is generally performed by a nurse, not an anesthesiologist, and the infusion is overseen by a psychiatrist and a nurse. Clinics led by anesthesiologists generally do not employ a staff psychiatrist but coordinate with the patients’ mental health practitioners.

Virtually all practitioners—anesthesiologists and psychiatrists alike—recognize the importance of cooperation. Nearly all ketamine clinics require a referral from a psychiatrist or other mental health professional, with few accepting walk-ins. “Three years ago, the relationships [between psychiatrists and anesthesiologists] were difficult, to say the least,” said anesthesiologist Mark Murphy, MD, who established Ketamine Wellness Centers in Phoenix, in 2013. “However, the momentum is shifting. Now we regularly receive referrals from mental health professionals.”

Those patients who do best tend to have psychiatrists or therapists supporting them throughout the treatment course and are engaged in a team approach, said anesthesiologist Isabel Legarda, MD, medical director at Boston MindCare LLC. “I believe anesthesiologists and psychiatrists must work collaboratively when it comes to ketamine infusion therapy; anything less shortchanges patients,” she said.

Insurance Coverage?

Because ketamine is generic, pharmaceutical companies have no financial incentive to sponsor the costly clinical trials needed to win FDA approval, generally a prerequisite for insurance coverage. Recognizing this, there is a movement in the ketamine community to gather and publish retrospective chart data and promulgate best practice guidelines. “There’s never going to be an FDA label for ketamine to treat depression,” said Dr. Levine. “But once more guidelines and protocols for using ketamine in clinical practice are published, it is very likely that insurers will consider covering it,” he predicted.

At least two drug companies are developing new ketamine variants that might be easier to administer and which lack some of the generic’s less-favorable short-term side effects, such as dissociation, and which insurers may be willing to cover. Johnson & Johnson’s subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals is conducting late-stage clinical trials of esketamine, a variant that can be administered via a nasal spray. The FDA granted the drug “breakthrough” status in 2013, which streamlines the regulatory approval process. Allergan’s subsidiary Naurex Inc. is testing GLYX-13, an IV NMDA receptor variant that reportedly is effective in about half of patients in 24 hours, but without ketamine’s dissociative side effects. NeuroRx Inc. is testing a drug, Cyclurad, whose ingredients include D-cycloserine, an NMDA receptor modulator.

Dr. Levine and other physicians caution colleagues against starting a ketamine clinic to make quick money. “If someone is thinking of doing this part time to pad their income, there could be bad outcomes because these patients are very vulnerable,” Dr. Levine said. “This is an area that could use some regulation and standardization so that patients don’t get hurt, and what is a very important treatment becomes lost.”

Most ketamine practitioners say their motivation stems from having had patients or family members who were treatment resistant and, in some cases, even committed suicide. For them, money is secondary to the satisfaction they gain. “For me, this has been a much more demanding and professionally rewarding practice than being in a hospital operating room,” said Dr. Brooks. “It requires a special dedication and availability.”

14/12/2013

Kétamine: Son intérêt en médecine de guerre

| Tags : kétamine

20/10/2012

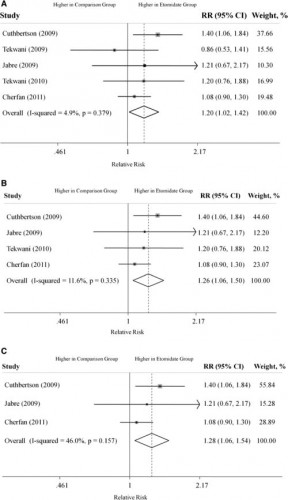

Etomidate: Encore une méta-analyse à charge

Etomidate is associated with mortality and adrenal insufficiency in sepsis: A meta-analysis.

Chee Man C. et all. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2945–2953

L'étude kETASED a confirmé l'intérêt du recours à la Kétamine chez le patient en défaillance vitale. Il existe une polémique concernant les effets délétères de l'étomidate sur la fonction corticosurrénalienne. Bien qu'une analyse récente n'ait pu l'objectiver après administration unique, la controverse continue. Une méta-analyse incluant chez 865 patients porteur de sepsis plaide pour l'existence d'une telle surmortalité.

On rappelle qu'en condition de combat, au delà de ce débat, l'agent d'induction de choix est la kétamine car son intérêt ne se limite pas à la simple induction. C'est aussi un agent de sédation et un antalgique.

30/04/2012

Sédation dissociative: La Kétamine

| Tags : kétamine

26/09/2011

Kétamine: Utilisation préhospitalière

| Tags : kétamine

17/10/2009

La kétamine pour l'intubation en séquence rapide

| Tags : kétamine, intubation

La kétamine pour l'humanitaire

| Tags : kétamine

La kétamine améliore la survie encondition expériementale

| Tags : kétamine