22/06/2016

AL pour intuber: A ressortir de l'oubli

The Myth of Rescue Reversal in “Can’t Intubate, Can’t Ventilate” Scenarios

Naguib N. et Al. Anesth Analg. 2016 Jul;123(1):82-92

__________________________

Ce travail met en avant l'insuffisance des démarches d'antagonisation pour restaurer une ventilation adéquate dans les situations de CICV. En ce qui concerne la gestion des voies aériennes en situation tactique, le principe de la préservation de la ventilation spontanée lors de l'accès aux voies aériennes mérite d'être rappelé. Si la réalisation d'une induction en séquence rapide reste la référence, en cas de difficulté prévisible le recours à une anesthésie locale doit être préférée (lire ce post).

Ceci est parfaitement stipulé dans les RFE "Sédation et analgésie en structure d’urgence" dont on rappelle après la présentation de l'abstract les termes de la question N3.

__________________________

BACKGROUND:

An unanticipated difficult airway during induction of anesthesia can be a vexing problem. In the setting of can't intubate, can't ventilate (CICV), rapid recovery of spontaneous ventilation is a reasonable goal. The urgency of restoring ventilation is a function of how quickly a patient's hemoglobin oxygen saturation decreases versus how much time is required for the effects of induction drugs to dissipate, namely the duration of unresponsiveness, ventilatory depression, and neuromuscular blockade. It has been suggested that prompt reversal of rocuronium-induced neuromuscular blockade with sugammadex will allow respiratory activity to recover before significant arterial desaturation. Using pharmacologic simulation, we compared the duration of unresponsiveness, ventilatory depression, and neuromuscular blockade in normal, obese, and morbidly obese body sizes in this life-threatening CICV scenario. We hypothesized that although neuromuscular function could be rapidly restored with sugammadex, significant arterial desaturation will occur before the recovery from unresponsiveness and/or central ventilatory depression in obese and morbidly obese body sizes.

METHODS:

We used published models to simulate the duration of unresponsiveness and ventilatory depression using a common induction technique with predicted rates of oxygen desaturation in various size patients and explored to what degree rapid reversal of rocuronium-induced neuromuscular blockade with sugammadex might improve the return of spontaneous ventilation in CICV situations.

RESULTS:

Our simulations showed that the duration of neuromuscular blockade was longer with 1.0 mg/kg succinylcholine than with 1.2 mg/kg rocuronium followed 3 minutes later by 16 mg/kg sugammadex (10.0 vs 4.5 minutes). Once rocuronium neuromuscular blockade was completely reversed with sugammadex, the duration of hemoglobin oxygen saturation >90%, loss of responsiveness, and intolerable ventilatory depression (a respiratory rate of ≤4 breaths/min) were dependent on the body habitus and duration of oxygen administration. There is a high probability of intolerable ventilatory depression that extends well beyond the time when oxygen saturation decreases <90%, especially in obese and morbidly obese patients. If ventilatory rescue is inadequate, oxygen desaturation will persist in the latter groups, despite full reversal of neuromuscular blockade. Depending on body habitus, the duration of intolerable ventilatory depression after sugammadex reversal may be as long as 15 minutes in 5% of individuals.

CONCLUSIONS:

The clinical management of CICV should focus primarily on restoration of airway patency, oxygenation, and ventilation consistent with the American Society of Anesthesiologist's practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. Pharmacologic intervention cannot be relied upon to rescue patients in a CICV crisis.

__________________________

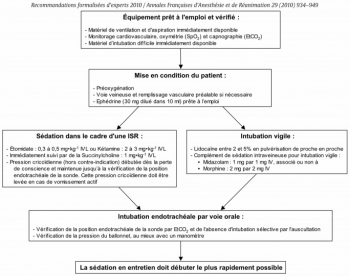

Question 3 - Intubation sous ISR et sous AL : Quelles sont les modalités de réalisation d’une sédation et/ou d’une analgésie pour l’intubation trachéale ?

Les experts recommandent d’administrer une sédation pour toutes les indications de l’intubation trachéale, excepté chez le patient en arrêt cardiaque qui ne nécessite pas de sédation. Lorsque l’intubation trachéale est présumée diffi cile, il est possible d’effectuer une anesthésie locale réalisée de proche en proche, associée ou non à une sédation légère et titrée par voie générale

L’utilisation de médicaments anesthésiques lors de l’intubation trachéale a pour but de faciliter le geste et d’assurer le confort du patient. Cette sédation doit être rapidement réversible pour restaurer une ventilation effi cace en cas de diffi culté d’intubation. Le risque d’inhalation bronchique doit être minimisé au cours de la procédure et ce d’autant que les patients sont considérés comme ayant un estomac plein.

Les experts recommandent d’utiliser les techniques d’intubation en séquence rapide (ISR) associant un hypnotique d’action rapide (étomidate ou kétamine) et un curare d’action brève (succinylcholine) ........................................................

Lorsque l’intubation trachéale est présumée difficile, le protocole recommandé par les experts pour une intubation vigile est le suivant : - Lidocaïne entre 2 et 5% en pulvérisation de proche en proche - Complément de sédation intraveineuse pour intubation vigile : • midazolam : 1 mg par 1 mg IV • associé ou non à de la morphine : 2 mg par 2 mg IV

Les commentaires sont fermés.