15/07/2015

Bilan US Afghanistan

Clic sur l'image pour accéder au document complet

Le résumé:

Introduction

The U.S. has achieved unprecedented survival rates, as high as 98%, for casualties arriving alive to the combat hospital. Our military medical personnel are rightly proud of this achievement. Commanders and service members are confident that if wounded and moved to a Role II or III medical facility, their care will be the best in the world. Combat casualty care however, begins at the point of injury and continues through evacuation to those facilities. With up to 25% of deaths on the battlefield being potentially preventable, the pre-hospital environment is the next frontier for making significant further improvements in battlefield trauma care. Strict adherence to the evidence-based Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Guidelines has been proven to reduce morbidity and mortality on the battlefield. However, full implementation across the entire force and commitment from both line and medical leadership continue to face ongoing challenges. This report on pre-hospital trauma in the Combined Joint Operations Area – Afghanistan (CJOA-A) is a follow-on to the one previously conducted in November 2012 and published in January 2013. Both assessments were conducted by the US Central Command (USCENTCOM) Joint Theater Trauma System (JTTS). Observations for this report were collected from December 2013 to January 2014 and were obtained directly from deployed prehospital providers, medical leaders, and combatant leaders. Significant progress has been made between these two reports with the establishment of a Pre-Hospital Care Division within the JTTS; development of a pre-hospital trauma registry and weekly pre-hospital trauma conferences; and CJOA-A theater guidance and enforcement of pre-hospital documentation. Specific pre-hospital trauma care achievements include expansion of transfusion capabilities forward to the point of injury, junctional tourniquets, and universal approval of tranexamic acid. CHANGING OLD PARADIGMS “Treat for shock, but do not waste any time doing it.” Fleet Marine Forces Manual “A tourniquet is a last resort for life-threatening Injuries. Tourniquets cut off blood flow to and from the extremity and are likely to cause permanent damage to vessels, nerves, and muscles.” AMEDDC&S Pamphlet No. 350-10 Saving Lives on the Battlefield (Part II) - One Year Later Unclassified 3 Unclassified

Observations & Discussion

TCCC Guidelines are widely, though not universally, accepted as Authoritative “best practices” for pre-hospital trauma care; however, they are not Directive policy. The high degree of variance amongst deployed unit medical personnel, both in terms of clinical training and operational experience, results in inconsistent application and enforcement of TCCC compliance across the force. Since our line commanders are dependent upon their unit medical personnel to inform their understanding, appreciation, and prioritization of medical support requirements, their TCCC commitment and command emphasis understandably varies as well. In the face of near-term resource constraints, without doctrinal and policy endorsement, the Services will continue to struggle to adequately and fully Organize, Train, and Equip to meet TCCC Guidelines as the standard for pre-hospital care. A previous memorandum and recommendation by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs to train all combatants and deployed medical personnel in TCCC remains incompletely implemented across the DoD. In contrast, US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) and US Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) have codified TCCC compliance as policy and reduced pre-hospital case fatality rates. We must continue to embrace and explore emerging capabilities to deliver far-forward resuscitative care. Those capabilities that are both responsive and adaptive to the dynamic tactical landscape hold the greatest intrinsic value for our line commanders and their personnel. We must also ensure that our supporting Organize, Train, and Equip functions have the agility to keep pace with these evolving standards of care. We must increase the investment in our medical personnel to develop and retain true expertise in pre-hospital trauma care delivery and oversight. These must become core competencies in the unique domain of operational medical support and we must embrace new medical training paradigms that advance these skills. Finally, officer professional development for both line and medical leaders must emphasize the shared responsibilities for developing and enforcing robust unit commitment to lifesaving pre-hospital trauma care principles.

Findings

1.The lack of standardized TCCC capability may represent a causal factor for the increased killed in action, case fatality rate, and preventable deaths seen in conventional forces when compared to special operations forces. 2. Absent a validated joint requirement which is captured doctrinally, the prevailing resourceconstrained environment will challenge Services to fully Organize, Train, and Equip to TCCC standards. Saving Lives on the Battlefield (Part II) - One Year Later Unclassified 4 Unclassified 3. There is no evidence that the DoD or CJOA-A has policies or procedures in place to validate or enforce pre-hospital care within an organization. Service-specific doctrine requiring Unit Surgeons to each establish a standard of care, allows for variant, non-standard delivery of battlefield trauma care across the force. Furthermore, even within a single command, rotation of Unit Surgeons introduces and magnifies discontinuity of unit trauma care standards. 4. The requirements to perform and support pre-hospital TCCC could be standardized across Services (universally or at the Combatant Command level) with the specific means to achieve these Train & Equip standards left up to the respective Services. 5. As with elements of pre-hospital care, organization structures are highly variant with a number of at-risk forces not having adequately manned/trained/equipped medical support. 6. Units with a tactical evacuation mission requirement should be task organized to be able to provide advanced enroute resuscitative care from the point of injury. 7. Robust training platforms exist for pre-hospital trauma care, though not all course training syllabi keep pace with current best practices. Sufficient information technologies exist to rapidly and widely disperse new TCCC Guidelines as they become immediately available. 8. Unit equipment sets and supporting medical logistics systems have not kept pace with evolving pre-hospital care TCCC guidelines. Out-dated items remain within the supply chain and newly required items have not yet been incorporated into standard configurations. 9. In the absence of a widely mandated policy that establishes TCCC Guidelines as the standard for pre-hospital battlefield care, and accountability for deviations from this standard, the degree of penetrance and acceptance of TCCC Guidelines will remain episodic and dependent upon individual (Surgeon and commander) commitment. 10. Neither line nor operational medical leaders are optimally prepared to recognize the importance of a robust, pre-hospital care system, or equipped with the requisite knowledge, skills, or experience to build or sustain such a system within their unit.

New Recommendations

1. DoD establishes TCCC Guidelines as the DoD standard of care for pre-hospital care. 2. DoD conducts a DOTMLPF-P assessment across Services to assess and implement TCCC Guideline capability. 3. DoD systematically review and correct all pre-hospital care doctrine across the spectrum to accurately represent TCCC Guidelines with the doctrine specifically stating “in accordance with Saving Lives on the Battlefield (Part II) - One Year Later Unclassified 5 Unclassified the current TCCC Guidelines published by the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care” to ensure that the doctrine remains current. 4. Services immediately implement an aggressive transition initiative to update all relevant medical equipment sets and medical logistic policies to ensure units have TCCC Guideline specified medical materials. 5. DoD establishes a Battlefield Pre-Hospital Trauma Care Program Proponent (or equivalent structure) in the DHA. 6. DoD develop and mandate a TCCC Accreditation, Certification, and Recertification program like Basic Life Support, Advanced Trauma Life Support, and Advanced Cardiac Life Support for all military personnel with a requirement for biannual re-certification and as based on level of ability and position (e.g. Non-Medical First Responder, Non-Medical Leader, Medical Provider, Medical Leader). 7. Services require and track TCCC certification for all pre-hospital medical personnel and integrate tracking into combatant Unit Status Reports. 8. Services incorporate TCCC Champion training into all basic and advanced officer and noncommissioned officer professional military development courses. 9. Services incorporate and mandate casualty management and hands on practical exercises into all professional military development courses. 10. DoD updates the Joint Capability Requirement for Tactical Enroute Care to include the ability to provide advanced resuscitative care from the point of injury. 11. As military physicians are ultimately responsible for assuming the role of EMS Director for pre-hospital services if assigned to a combatant unit, the military Services should study and develop career, educational and assignment tracks for operational medical corps officers which includes emphasis upon pre-hospital care delivery.

Conclusion

History teaches that the lessons we have learned regarding combat casualty care may be lost if we fail to attend to them in the coming years. Even in a resource-constrained future, the MHS has the necessary raw materials of personnel, organization, and experience to retain and refine our current best practices. With continued efforts aimed at 1) formalizing TCCC Guideline compliance across the force; 2) embracing evidence-based methods to continually improve upon these Guidelines; and 3) selecting, developing and retaining operational medical personnel dedicated to pre-hospital trauma care, the MHS will ensure an organizational culture that fully embraces pre-hospital combat casualty care as a core competency.

| Tags : tccc

14/07/2015

Intranasal ? sans hésiter !

| Tags : intranasal

11/07/2015

ATLS: Une vision archaïque ?

ATLS: Archaic Trauma Life Support?

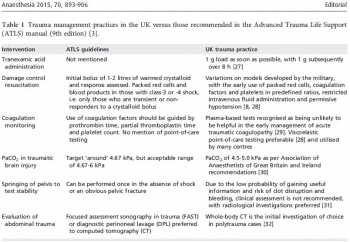

Wiles MD Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 893–906

--------------------------------------------------

Un éditorial décoifffant mais pas tant que cela. Une revue cochrane récente ne trouvait pas d'argument en faveur de l'intérêt de l'ATLS (1). Le bien fondé de ce type de fromation est très débattue dans les pays disposant d'une structure spécialisée de prise en charge de traumatisé( 2). Peu étonnant quand on connait l'histoire de l'ATLS censé apporter des connaissances et une méthode à des personnels et des structures hospitalières non spécialisées en traumatologie. Les conclusions de cet éditorial repositionne très bien ce type de formations courtes

--------------------------------------------------

No one could have imagined that when a light aircraft crashed in rural Nebraska in 1976, the nature of global trauma management would be forever altered. James Styner, an orthopaedic surgeon, was piloting the plane in question and the accident resulted in the death of his wife and serious injuries to himself and his four children. The standard of care that he and his family received in the local hospital in the aftermath of the crash so horrified Styner that he decided to establish a new system for the management of major trauma...........................

......So what direction should trauma training take in the future?

I would suggest the following:

1 Treat ATLS as a ‘basic’ trauma course, with attendance limited to junior medical staff with no trauma experience. Candidates will learn the common language and vocabulary of trauma management, which will be of benefit when they subsequently attend trauma calls in clinical practice. In the developing world, where resources and personnel are limited, ATLS will continue to have a role.

2 Stop routine recertification of ATLS for individuals experienced in trauma management. Given the high cost of these courses (~£600 (€825; $918) for certification and £350 (€482; $535) for recertification) this practice will account for a significant proportion of an individual’s annual study leave budget. This time and money would be better invested in developing enhanced leadership, communication and teamworking skills.

3 In line with the Royal College of Anaesthetists, remove ATLS certification as a prerequisite for the completion of training in surgery and emergency medicine. Instead, focus on ensuring adequate experience in the management of major trauma.

4 Similarly, for consultant posts that include trauma management, remove ATLS certification as an appointment criterion.

Evidence of experience in trauma management, alongside formal training in leadership and/or human factors, would be of greater relevance.

5 Require regular team-training sessions for MTC staff, either by video review or utilising simulation, ideally within the team’s usual working environment. This would allow training to be institution-specific, with the potential to refine protocols and undertake focused debriefs of recent cases.

When introduced almost 40 years ago, ATLS represented the cutting edge of trauma management; unfortunately, the course has failed to evolve at a pace that allows it to be relevant to the care delivered in modern MTCs. This course without doubt revolutionised trauma care, but it should now be reserved for use in isolated rural centres or environments where trauma is managed infrequently and with limited resources. The King is dead, long live the King.

10/07/2015

Le point sur la réalité du TCCC US

07/07/2015

Quelle attelle de fémur ?

Evaluation of commercially available traction splints for battlefield use

Studer NM et All. J Spec Oper Med. 2014 Summer;14(2):46-55

------------------------------------------------------

L'immobilisation d'une fracture de fémur nécessite idéalement une traction. Les attelles de type thomas-lardenois ne sont pas utilisables en préhospitalier. La classique attelle de Donway n'est pas idéale dès lors que l'on est en combat à pied. Bien que l'intérêt de telles attelles reste discuté (1) , nous disposons à la nomenclature de l'atelle Faretec CT6. Le document présenté vante de manière très surprenante les qualités de l'attelle de slishman. Certes cette dernière semble plus rapide à poser mais avec un taux d'échec beaucoup plus important. La CT6 reste donc un excellent choix, c'est d'ailleurs ce qui est également dit dans ce document qui parait quelque peu orienté dans ces conclusions.

------------------------------------------------------

Background: Femoral fracture is a common battlefield injury with grave complications if not properly treated. Traction splinting has been proved to decrease morbidity and mortality in battlefield femur fractures. However, little standardization of equipment and training exists within the United States Armed Forces. Currently, four traction splints that have been awarded NATO Stock Numbers are in use: the CT-6 Leg Splint, the Kendrick Traction Device (KTD), the REEL Splint (RS), and the Slishman Traction Splint (STS).

Objective: The purpose of this study was to determine the differences between the four commercially available traction devices sold to the U.S. Government.

Methods: After standardized instruction, subjects were timed and evaluated in the application of each of the four listed splints. Participant confidence and preferences were assessed by using Likertscaled surveys. Free response remarks were collected before and after timed application.

Results: Subjects had significantly different application times on the four devices tested (analysis of variance [ANOVA], p < .01). Application time for the STS was faster than that for both the CT-6 (t-test, p < .0028) and the RS (p < .0001). Subjects also rated the STS highest in all post-testing subjective survey categories and reported significantly higher confidence that the STS would best treat a femoral fracture (p < .00229).

Conclusions: The STS had the best objective performance during testing and the highest subjective evaluation by participants. Along with its ability to be used in the setting of associated lower extremity amputation or trauma, this splint is the most suitable for battlefield use of the three devices tested

| Tags : immobilisation

03/07/2015

Coniotomie: improviser ?

| Tags : coniotomie

Fibrinogène avec le TXA ?: Plutôt oui

Association of Cryoprecipitate and Tranexamic Acid With Improved Survival Following Wartime Injury: Findings From the MATTERs II Study

Morrison JJ et Al. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(3):218-225.

Objective To quantify the impact of fibrinogen-containing cryoprecipitate in addition to the antifibrinolytic tranexamic acid on survival in combat injured.

Design Retrospective observational study comparing the mortality of 4 groups: tranexamic acid only, cryoprecipitate only, tranexamic acid and cryoprecipitate, and neither tranexamic acid nor cryoprecipitate. To balance comparisons, propensity scores were developed and added as covariates to logistic regression models predicting mortality.

Setting A Role 3 Combat Surgical Hospital in southern Afghanistan.

Patients A total of 1332 patients were identified from prospectively collected UK and US trauma registries who required 1 U or more of packed red blood cells and composed the following groups: tranexamic acid (n = 148), cryoprecipitate (n = 168), tranexamic acid/cryoprecipitate (n = 258), and no tranexamic acid/cryoprecipitate (n = 758).

Main Outcome Measure In-hospital mortality.

Results Injury Severity Scores were highest in the cryoprecipitate (mean [SD], 28.3 [15.7]) and tranexamic acid/cryoprecipitate (mean [SD], 26 [14.9]) groups compared with the tranexamic acid (mean [SD], 23.0 [19.2]) and no tranexamic acid/cryoprecipitate (mean [SD], 21.2 [18.5]) (P < .001) groups. Despite greater Injury Severity Scores and packed red blood cell requirements, mortality was lowest in the tranexamic acid/cryoprecipitate (11.6%) and tranexamic acid (18.2%) groups compared with the cryoprecipitate (21.4%) and no tranexamic acid/cryoprecipitate (23.6%) groups. Tranexamic acid and cryoprecipitate were independently associated with a similarly reduced mortality (odds ratio, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.42-0.89; P = .01 and odds ratio, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.40-0.94; P = .02, respectively). The combined tranexamic acid and cryoprecipitate effect vs neither in a synergy model had an odds ratio of 0.34 (95% CI, 0.20-0.58; P < .001), reflecting nonsignificant interaction (P = .21).

Conclusions Cryoprecipitate may independently add to the survival benefit of tranexamic acid in the seriously injured requiring transfusion. Additional study is necessary to define the role of fibrinogen in resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock.

| Tags : coagulopathie

02/07/2015

Evasan stratégiques: Que fait on ?

| Tags : evasan

Hémorragie jonctionnelle: Croc ou Sam Tourniquet ?

| Tags : jonctionnel