11/07/2015

ATLS: Une vision archaïque ?

ATLS: Archaic Trauma Life Support?

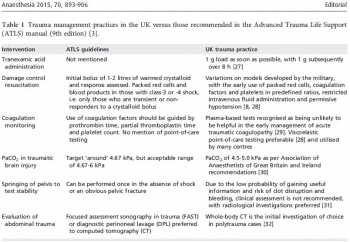

Wiles MD Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 893–906

--------------------------------------------------

Un éditorial décoifffant mais pas tant que cela. Une revue cochrane récente ne trouvait pas d'argument en faveur de l'intérêt de l'ATLS (1). Le bien fondé de ce type de fromation est très débattue dans les pays disposant d'une structure spécialisée de prise en charge de traumatisé( 2). Peu étonnant quand on connait l'histoire de l'ATLS censé apporter des connaissances et une méthode à des personnels et des structures hospitalières non spécialisées en traumatologie. Les conclusions de cet éditorial repositionne très bien ce type de formations courtes

--------------------------------------------------

No one could have imagined that when a light aircraft crashed in rural Nebraska in 1976, the nature of global trauma management would be forever altered. James Styner, an orthopaedic surgeon, was piloting the plane in question and the accident resulted in the death of his wife and serious injuries to himself and his four children. The standard of care that he and his family received in the local hospital in the aftermath of the crash so horrified Styner that he decided to establish a new system for the management of major trauma...........................

......So what direction should trauma training take in the future?

I would suggest the following:

1 Treat ATLS as a ‘basic’ trauma course, with attendance limited to junior medical staff with no trauma experience. Candidates will learn the common language and vocabulary of trauma management, which will be of benefit when they subsequently attend trauma calls in clinical practice. In the developing world, where resources and personnel are limited, ATLS will continue to have a role.

2 Stop routine recertification of ATLS for individuals experienced in trauma management. Given the high cost of these courses (~£600 (€825; $918) for certification and £350 (€482; $535) for recertification) this practice will account for a significant proportion of an individual’s annual study leave budget. This time and money would be better invested in developing enhanced leadership, communication and teamworking skills.

3 In line with the Royal College of Anaesthetists, remove ATLS certification as a prerequisite for the completion of training in surgery and emergency medicine. Instead, focus on ensuring adequate experience in the management of major trauma.

4 Similarly, for consultant posts that include trauma management, remove ATLS certification as an appointment criterion.

Evidence of experience in trauma management, alongside formal training in leadership and/or human factors, would be of greater relevance.

5 Require regular team-training sessions for MTC staff, either by video review or utilising simulation, ideally within the team’s usual working environment. This would allow training to be institution-specific, with the potential to refine protocols and undertake focused debriefs of recent cases.

When introduced almost 40 years ago, ATLS represented the cutting edge of trauma management; unfortunately, the course has failed to evolve at a pace that allows it to be relevant to the care delivered in modern MTCs. This course without doubt revolutionised trauma care, but it should now be reserved for use in isolated rural centres or environments where trauma is managed infrequently and with limited resources. The King is dead, long live the King.

Les commentaires sont fermés.