----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

15/02/2011

Intubation préhospitalière: Que penser de l'AIRTRAQ ?

Comme pour tout il faut s'entraîner et on n'inove pas. On rappelle que, en conditions de combat, le contrôle des voies aériennes a pour but essentiellemment de prévenir l'obstruction des voies aériennes, de prévenir l'inhalation du contenu gastrique. Le traitement d'une détresse respiratoire fait appel avant tout à l'oxygénothérapie si vous disposez d'oxygène, au traitement d'une cause spécifique (pneumo ou hémothorax, volet thoracique, plaie soufflante), à l'assistance ventilatoire au ballon par masque facial et EVENTUELLEMENT après intubation ou coniotomie sur une canule de 6 mm si les conditions tactiques le permettent.

Use of the Airtraq laryngoscope for emergency intubation in the prehospital setting: A randomized control trial

Trimmel H et all.

Crit Care Med 2011 Vol. 39, No. 3, 1-5

Objectives: The optical Airtraq laryngoscope (Prodol Meditec, Vizcaya, Spain) has been shown to have advantages when compared with direct laryngoscopy in difficult airway patients. Furthermore, it has been suggested that it is easy to use and handle even for inexperienced advanced life support providers. As such, we sought to assess whether the Airtraq may be a reliable alternative to conventional intubation when used in the prehospital setting.

Design, Setting, and Patients: Prospective, randomized control trial in emergency patients requiring endotracheal intubation provided by anesthesiologists or emergency physicians responding with an emergency medical service helicopter or ground unit associated with the Department of Anesthesiology, General Hospital, Wiener Neustadt, Austria.

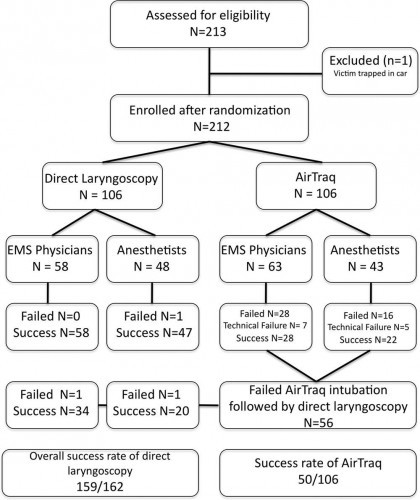

Measurements and Main Results: During the 18-month study period, 212 patients were enrolled. When the Airtraq was used as first-line airway device (n = 106) vs. direct laryngoscopy (n =106), success rate was 47% vs. 99%, respectively (p < .001). Reasons for failed Airtraq intubation were related to the fiberoptic characteristic of this device (i.e., impaired sight due to blood and vomitus, n = 11) or to assumed handling problems (i.e., cuff damage, tube misplacement, or inappropriate visualization of the glottis, n = 24). In 54 of 56 patients where Airtraq intubation failed, direct laryngoscopy was successful on the first attempt; in the remaining two and in one additional case of failed direct laryngoscopy, the airway was finally secured employing the Fastrach laryngeal mask. There was no correlation between success rates and body mass index, age, indication for airway management, emergency medical service unit, or experience of the physicians.

Conclusions: Based on these results, the use of the Airtraq laryngoscope as a primary airway device cannot be recommended in the prehospital setting without significant clinical experience obtained in the operation room. We conclude that the clinical learning process of the Airtraq laryngoscope is much longer than reported in the anesthesia literature.

| Tags : intubation, airway

05/02/2011

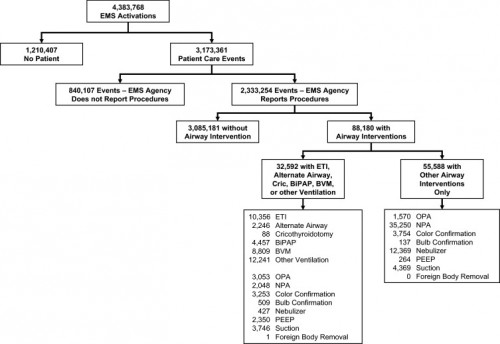

Etude NEMESIS: Out-of-hospital airway management in the United States

Un travail prospectif recensant toutes les manoeuvres de contrôle des voies aériennes aux USA vient d'être publié ( Out-of-hospital airway management in the United States - Wang HE et all. -doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.12.014). Ce document est intéressant car il confirme que l'intubation est le mode premier de contrôle de la ventilation aux USA suivi par la ventilation manuelle au ballon. Le recours à des disposiifs laryngés ne vient qu'au 4ème rang après la mise en oeuvre de technqiues de ventilation non invasive. L'apprentissage de l'intubation reste donc un objectif essentiel. Les tableaux suivant en présentent les principaux résultats.

Table 1. Prevalence of airway management interventions. Table includes only EMS agencies reporting at least one procedure in the NEMSIS 2008 data set. Percentages reflect portion of 2,333,254 total patient care events. Prevalence estimates not calculated for King LT and foreign body removal due to the small numbers of events. BiPAP = bilevel positive airway pressure. CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure. PEEP = positive end expiratory pressure.

| Intervention | N | (N per 100,000 care events; 95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Bag-valve-mask ventilation | 8809 | (378; 370–386) |

| Other ventilation (bag-valve, mechanical, unspecified) | 12,241 | (525; 516–534) |

| Endotracheal intubation | 10,356 | (444; 436–453) |

| Orotracheal intubation | 9130 | (392; 384–400) |

| Nasotracheal intuabtion | 1064 | (46; 43–48) |

| Rapid sequence intubation | 371 | (16; 14–18) |

| Alternate airway | 2246 | (96; 92–100) |

| Combitube | 1521 | (65; 62–69) |

| Esophageal-Obturator Airway (EOA) | 175 | (8; 6–9) |

| Laryngeal Mask Airway | 571 | (24; 23–27) |

| King LT | 4 | (Not calculated) |

| Cricothyroidotomy | 88 | (4; 3–5) |

| BiPAP/CPAP | 4456 | (191; 186–197) |

| Oropharyngeal airway | 4623 | (198; 193–204) |

| Nasopharyngeal airway | 37,298 | (160; 158–161) |

| Colorimetric tube confirmation | 7007 | (300; 294–308) |

| Bulb tube confirmation | 646 | (28; 26–30) |

| Nebulizer | 12,796 | (549; 539–558) |

| PEEP | 2614 | (112; 108–117) |

| Suction | 8115 | (348; 341–356) |

| Foreign body removal | 1 | (Not calculated) |

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Table 3. Airway intervention success. Includes only orotracheal, nasotracheal and rapid sequence intubation and alternate airway insertions where procedural success was reported. ETI success was reported for only 8418 of 10,356 ETI.

ETI = endotracheal intubation. US = United States.

a Subgroups do not add up to total because of unknown cardiac arrest status for 5244 cases. Univariable odds ratios presented for selected comparisons only.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Abstract

-----Among 4,383,768 EMS activations, there were 10,356 ETI, 2246 alternate airways, and 88 cricothyroidotomies. ETI success rates were: overall 6482/8418 (77.0%; 95% CI: 76.1–77.9%), cardiac arrest 3494/4482 (78.0%), non-arrest medical 616/846 (72.8%), non-arrest injury 417/505 (82.6%), children <10 years 295/397 (74.3%), children 10–19 years 228/289 (78.9%), adult 5829/7552 (77.2%), and rapid-sequence intubation 289/355 (81.4%). ETI success was success was lowest in the South US census region. Alternate airway success was 1564/1794 (87.2%). Major complications included: bleeding 84 (7.0 per 1000 interventions), vomiting 80 (6.7 per 1000) and esophageal intubation 12 (1.0 per 1000).

Conclusions

In this study characterizing out-of-hospital airway management across the United States, we observed low out-of-hospital ETI success rates. These data may guide national efforts to improve the quality of out-of-hospital airway management.

| Tags : airway, intubation

Brancard d'extraction: Le Snigel design

| Tags : brancardage, extraction

Brancard d'extraction: Pc Kit de la société Fenton Medical

Vous utilisez problement le filet golanis dont l'intérêt en terme de poids est connu mais aussi ses limites pour un brancardage un peu long. Ce produit est une alternative

Pour plus d'informations

| Tags : brancardage, extraction