06/03/2017

PTSD: Les soignants aussi

PTSD in those who care for the injured

Luftman K. et Al. Injury, Int. J. Care Injured 48 (2017) 293–296

-------------------------------------

PTSD, les soignants aussi. Cela peut paraître évident mais ce qui interpelle, c'est l'importance du phénomène.

---------------------------------------

Background: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) has become a focus for the care of trauma victims, but the incidence of PTSD in those who care for injured patients has not been well studied. Our hypothesis was that a significant proportion of health care providers involved with trauma care are at risk of developing PTSD.

Methods: A system-wide survey was applied using a modified version of the Primary Care PTSD Screen [PC-PTSD], a validated PTSD screening tool currently being used by the VA to screen veterans for PTSD. Pre-hospital and in-hospital care providers including paramedics, nurses, trauma surgeons, emergency medicine physicians, and residents were invited to participate in the survey. The survey questionnaire was anonymously and voluntarily performed online using the Qualtrix system. Providers screened positive if they affirmatively answered any three or more of the four screening questions and negative if they answered less than three questions with a positive answer. Respondents were grouped by age, gender, region, and profession.

Results: 546 providers answered all of the survey questions. The screening was positive in 180 (33%) and negative in 366 (67%) of the responders. There were no differences observed in screen positivity for gender, region, or age. Pre-hospital providers were significantly more likely to screen positive for PTSD compared to the in-hospital providers (42% vs. 21%, P < 0.001). Only 55% of respondents had ever received any information or education about PTSD and only 13% of respondents ever sought treatment for PTSD.

Conclusion: The results of this survey are alarming, with high proportions of healthcare workers at risk for PTSD across all professional groups. PTSD is a vastly underreported entity in those who care for the injured and could potentially represent a major problem for both pre-hospital and in-hospital providers. A larger, national study is warranted to verify these regional results

| Tags : ptsd

17/09/2016

La Kétamine prévient-elle le PTSD ?

| Tags : ptsd

01/08/2016

La guerre, et après ?

| Tags : ptsd

03/01/2016

Kétamine: Prudence quand même

Is ketamine ready to be used clinically for the treatment of depression ?

Colleen L. Med J Aust 2015 Dec 14;203(11):425.

A single dose of ketamine produces rapid antidepressant effects, but attaining lasting remission remains a challenge

Il existe un engouement très important pour l'emploi de kétamine pour la prise en charge de la dépression (1,2). Pour autant il ne faut pas oublier les effets secondaires de cette dernière lorsqu'elle est administrée de manière chronique. De nombreuses données issues de l'emploi récréatif de la kétamine mettent en avant de nombreux effets secondaires comme l'hépatotoxicité, les dysfonctions vésicales et, possiblement des troubles cognitifs. Même si aucun effets de ce type n'est retrouvé lors d'emploi encadré médicalement, la prudence reste de mise.

01/01/2016

Kétamine et dépression: Raz de marée

Anesthesiologists Take Lead As Ketamine Clinics Proliferate

A growing number of anesthesiologists are opening private clinics that provide off-label infusions of ketamine to patients suffering from treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, suicidality and other disorders. Psychiatrists and other physicians have also recently opened clinics.

The cost per infusion ranges from $400 to $1700, with most clinics charging about $500. Patients pay out-of-pocket since most health insurance plans do not cover the off-label procedure.

Despite the cost, patients seek the treatments after their antidepressants and other therapies prove ineffective. Proponents claim that, when administered as an IV infusion in a subanesthetic dose (typically 0.5 mg/kg body weight) over 40 to 45 minutes, ketamine begins reversing symptoms of depression for two of three patients in less than 24 hours, with effects persisting for a week or more. Nearly three of four patients suffering from suicidality experience an almost immediate reversal in thinking.

“The results are amazing,” said anesthesiologist Glen Z. Brooks, MD, founder and medical director of New York Ketamine Infusions LLC, in New York City, and one of the pioneers in the field. His success rate averages about 65% when measured by standardized mood and function surveys, and is even greater for younger adults, he said. The typical course of treatment is six infusions administered every other day for two weeks followed by “maintenance” or “booster” infusions as needed, typically every six weeks afterward.

“The procedure is very well tolerated. We have seen no complications during or after the 45-minute infusions in now close to 8,000 treatments,” Dr. Brooks told Anesthesiology News. “I have been treating some patients for as long as three years with ongoing remission of their symptoms, so efficacy can be very long term.”

Ketamine Can Work Quickly

Ketamine was synthesized in the early 1960s and approved for human anesthesia a decade later. It has been administered to millions of patients worldwide, and continues to be an anesthetic of choice for pediatric patients who may experience adverse reactions to other agents. It also is used in pain clinics and when changing dressings of severe burn victims.

For treating depression, it only takes two ketamine infusions to determine whether a patient will respond favorably, whereas traditional antidepressants can take four to six weeks and will work about 30% of the time. During the ketamine infusion, patients remain awake or in a twilight state. Dizziness or a sensation of dissociation is common, and generally disappears shortly after the infusion. “We notice a 50% improvement in depression scores within the first three infusions, which take six days,” said anesthesiologist Enrique Abreu, MD, medical director at Portland Ketamine Clinic in Oregon. “Overall, 75% to 80% of patients see improvement in depression, mood and anxiety after six treatments,” he told Anesthesiology News.

Some experts in depression research have called ketamine’s “rapid and robust” antidepressant properties “arguably the most important discovery in half a century” (Science 2012;338:68-72). Others urge caution, citing concerns over long-term side effects and potential for abuse. The latter concern stems from ketamine being an illicit “rave” drug (nicknamed “Special K” or “Vitamin K”) that creates intense, short-term hallucinations, dissociation and psychotomimetic effects. Ketamine also is pharmacologically similar to PCP (phencyclidine), a powerful psychotomimetic drug.

While the World Health Organization has long included ketamine on its model list of essential medicines for anesthesia, the drug also has been placed under national control in more than 60 countries, especially in Asia, where abuse is common. Bladder problems and cognitive declines have been observed in long-term recreational ketamine abusers, but none of these effects has been observed in clinical trials.

The anesthesiologists and psychiatrists who administer ketamine infusions for severe depression report overwhelmingly positive outcomes. New Jersey psychiatrist Steven Levine, MD, decided to explore ketamine after reading reports of clinical studies conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). “The results were unlike anything we had seen before, with positive outcomes emerging within days or weeks,” Dr. Levine said. “Some really sick people were getting significantly better within hours. I couldn’t convince myself to not do it.”

Dr. Levine quizzed several anesthesiologist friends about potential dangers before opening his clinic. “They were totally nonplussed about the low dosage used in the infusion, unconcerned about any potential for bad side effects,” Dr. Levine told Anesthesiology News. “They were used to giving it in much higher doses for anesthesia and even higher doses in burn units when changing dressings.” Dr. Levine opened Ketamine Treatment Centers of Princeton LLC, in New Jersey, in 2011 and has since treated about 500 patients. He plans to open clinics in Baltimore, Florida and Denver in early 2016.

Mechanisms of Action

Typical FDA-approved antidepressants target neurons that inhibit the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. Ketamine works more broadly by blocking the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, a component of the fast-signaling glutamate system that affects nearly all neurons. Brain scans reveal that ketamine rapidly induces synaptogenesis, repairing damage caused by chronic stress.

Many clinical trials of ketamine for depression have been, and continue to be, conducted at NIMH. A seminal study published in 2006 was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover trial led by Carlos A. Zarate Jr., MD, chief of NIMH’s neurobiology and mood disorders treatment section. In this year-long study, patients receiving ketamine showed significant improvement in depression compared with placebo after 24 hours, with effects remaining “moderate to large” after one week (Arch Gen Psych 2006;63:856-864). “This line of research holds considerable promise for developing new treatments for depression with the potential to alleviate much of the morbidity and mortality associated with the delayed onset of action of traditional antidepressants,” Dr. Zarate and colleagues wrote, citing the need to improve the drug’s long-term effectiveness.

Since then, studies at NIMH and elsewhere have demonstrated ketamine’s efficacy for rapidly diminishing suicidal ideation (Drugs R D 2015;15:37-43), unipolar and bipolar depression (Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;23:CD011612; Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;29:CD-011611), and for PTSD and other anxiety disorders (JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:681-688).

The American Psychiatric Association’s Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments urges caution when it comes to clinical use of ketamine. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of ketamine and other NMDA receptor antagonists (Am J Psych 2015;172:950-966), the task force concluded: “The antidepressant efficacy of ketamine … holds promise for future glutamate-modulating strategies.” However, the “fleeting nature of ketamine’s therapeutic benefit, coupled with its potential for abuse and neurotoxicity, suggest that its use in the clinical setting warrants caution.”

When asked to comment on anesthesiologists performing off-label ketamine infusions, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) provided this statement to Anesthesiology News: “The American Society of Anesthesiologists is committed to promoting the highest standards of care for the patients they serve. This new practice area has been brought to ASA’s attention and will be carefully reviewed.”

Gaining Legitimacy

According to ketamine advocate Dennis Hartman, at least 60 private clinics in the United States offer off-label infusions, and the number is growing. The former business executive says ketamine infusions rescued him from suicide in 2012, and ongoing treatments have brought his depression into remission. As founder and CEO of the nonprofit Ketamine Advocacy Network, Mr. Hartman now works full time with practitioners and patients to help gain legitimacy for the field. His website lists 18 ketamine practitioners in the United States, most of them anesthesiologists, with a smaller number of psychiatrists and neurologists, plus one emergency medicine physician and one family physician.

“There are others that we have not vetted and others that we’ve purposefully chosen not to include,” Mr. Hartman explained, most often because they charge too much money or require expensive additional tests or medical procedures for which clinical evidence is lacking. “There are still others who offer the treatment but want to be under the radar,” Mr. Hartman told Anesthesiology News.

Anesthesiologists generally believe they are uniquely qualified to administer ketamine infusions because of their expertise with anesthetics. “I want this to stay as something for anesthesiologists,” said Steven Mandel, MD, founder of Ketamine Clinics of Los Angeles. “Nevertheless, I don’t want there to be a conflict between anesthesiology and psychiatry, because ketamine definitely needs an anesthesiologist to administer it and definitely needs a psychiatrist or psychologist involved because they know about psychopathology,” he said. But ketamine does take “considerable vigilance and finesse” to infuse properly, he added, even for those with years of operating room experience. “This is different because the ‘sweet spot’ for treatment is this side of unconsciousness in the moderate- to deep-sedation range,” Dr. Mandel explained.

Many psychiatrists, on the other hand, believe they are best suited to oversee ketamine therapy because of their expertise in treating patients with depression, PTSD and other conditions. In those ketamine clinics run by psychiatrists, the IV insertion is generally performed by a nurse, not an anesthesiologist, and the infusion is overseen by a psychiatrist and a nurse. Clinics led by anesthesiologists generally do not employ a staff psychiatrist but coordinate with the patients’ mental health practitioners.

Virtually all practitioners—anesthesiologists and psychiatrists alike—recognize the importance of cooperation. Nearly all ketamine clinics require a referral from a psychiatrist or other mental health professional, with few accepting walk-ins. “Three years ago, the relationships [between psychiatrists and anesthesiologists] were difficult, to say the least,” said anesthesiologist Mark Murphy, MD, who established Ketamine Wellness Centers in Phoenix, in 2013. “However, the momentum is shifting. Now we regularly receive referrals from mental health professionals.”

Those patients who do best tend to have psychiatrists or therapists supporting them throughout the treatment course and are engaged in a team approach, said anesthesiologist Isabel Legarda, MD, medical director at Boston MindCare LLC. “I believe anesthesiologists and psychiatrists must work collaboratively when it comes to ketamine infusion therapy; anything less shortchanges patients,” she said.

Insurance Coverage?

Because ketamine is generic, pharmaceutical companies have no financial incentive to sponsor the costly clinical trials needed to win FDA approval, generally a prerequisite for insurance coverage. Recognizing this, there is a movement in the ketamine community to gather and publish retrospective chart data and promulgate best practice guidelines. “There’s never going to be an FDA label for ketamine to treat depression,” said Dr. Levine. “But once more guidelines and protocols for using ketamine in clinical practice are published, it is very likely that insurers will consider covering it,” he predicted.

At least two drug companies are developing new ketamine variants that might be easier to administer and which lack some of the generic’s less-favorable short-term side effects, such as dissociation, and which insurers may be willing to cover. Johnson & Johnson’s subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals is conducting late-stage clinical trials of esketamine, a variant that can be administered via a nasal spray. The FDA granted the drug “breakthrough” status in 2013, which streamlines the regulatory approval process. Allergan’s subsidiary Naurex Inc. is testing GLYX-13, an IV NMDA receptor variant that reportedly is effective in about half of patients in 24 hours, but without ketamine’s dissociative side effects. NeuroRx Inc. is testing a drug, Cyclurad, whose ingredients include D-cycloserine, an NMDA receptor modulator.

Dr. Levine and other physicians caution colleagues against starting a ketamine clinic to make quick money. “If someone is thinking of doing this part time to pad their income, there could be bad outcomes because these patients are very vulnerable,” Dr. Levine said. “This is an area that could use some regulation and standardization so that patients don’t get hurt, and what is a very important treatment becomes lost.”

Most ketamine practitioners say their motivation stems from having had patients or family members who were treatment resistant and, in some cases, even committed suicide. For them, money is secondary to the satisfaction they gain. “For me, this has been a much more demanding and professionally rewarding practice than being in a hospital operating room,” said Dr. Brooks. “It requires a special dedication and availability.”

26/11/2015

Kétamine pour le PTSD: Oui!

Efficacy of Intravenous Ketamine for Treatment of Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. A Randomized Clinical Trial

Feder A. et Al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 Jun;71(6):681-8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.62

Importance Few pharmacotherapies have demonstrated sufficient efficacy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a chronic and disabling condition.

Objective To test the efficacy and safety of a single intravenous subanesthetic dose of ketamine for the treatment of PTSD and associated depressive symptoms in patients with chronic PTSD.

Design, Setting, and Participants Proof-of-concept, randomized, double-blind, crossover trial comparing ketamine with an active placebo control, midazolam, conducted at a single site (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York). Forty-one patients with chronic PTSD related to a range of trauma exposures were recruited via advertisements.

Interventions Intravenous infusion of ketamine hydrochloride (0.5 mg/kg) and midazolam (0.045 mg/kg).

Main Outcomes and Measures The primary outcome measure was change in PTSD symptom severity, measured using the Impact of Event Scale–Revised. Secondary outcome measures included the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Clinical Global Impression–Severity and –Improvement scales, and adverse effect measures, including the Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, and the Young Mania Rating Scale.

Results Ketamine infusion was associated with significant and rapid reduction in PTSD symptom severity, compared with midazolam, when assessed 24 hours after infusion (mean difference in Impact of Event Scale–Revised score, 12.7 [95% CI, 2.5-22.8]; P = .02). Greater reduction of PTSD symptoms following treatment with ketamine was evident in both crossover and first-period analyses, and remained significant after adjusting for baseline and 24-hour depressive symptom severity. Ketamine was also associated with reduction in comorbid depressive symptoms and with improvement in overall clinical presentation. Ketamine was generally well tolerated without clinically significant persistent dissociative symptoms.

Conclusions and Relevance This study provides the first evidence for rapid reduction in symptom severity following ketamine infusion in patients with chronic PTSD. If replicated, these findings may lead to novel approaches to the pharmacologic treatment of patients with this disabling condition.

| Tags : ptsd

08/12/2013

PTSD et armée anglaise: Touchée comme tout le monde

PTSD in the armed forces: What have we learned from the recent cohort studies of Iraq/Afghanistan?

Goodwin L. et Al. Journal of Mental Health, 2013; 22(5): 397–401

L'armée anglaise semblait préservée du PTSD dans son expérience irakienne: Pas plus de PTSD que dans les troupes non déployées (1). Les explications semblaient se situer au niveau d'une organisation différente (taux d'encadrement, soldats plus âgés, et mission plus courtes). Les choses ont bien changées et actuellement nos alliées sont confrontés aux même problème que nous (2). Il est constaté un taux de PTSD double chez les réservistes engagés (3), par ailleurs ces troubles apparaissent plus tôt et chez des combattants plus jeunes que dans les conflits précédents (4) Le travail présenté fait le point de l'expérience actuelle en la matière des psychiatres militaires anglais

----------------------------------------------

In conclusion, the developments in military epidemiology have allowed cohort studies to confirm that combat experience is temporally related to PTSD. Yet, the majority of those who are deployed seem to be resilient. Across studies there are other common prospective vulnerability factors for PTSD, including psychiatric co-morbidity, alcohol misuse and lack of support. Whilst cross-sectional studies have found evidence to suggest that events outside of the military are important risks for PTSD, this needs to be investigated further in longitudinal research. Delayed-onset PTSD and other symptom trajectories which increase following deployment may be most important from a military perspective, but there is a need to further understand the reasons for the observed heterogeneity of PTSD trajectories.

----------------------------------------------

| Tags : ptsd

02/10/2013

Mental health following traumatic physical injury: An integrative literature review

Mental health following traumatic physical injury: An integrative literature review

Wiseman T et All. Injury, Int. J. Care Injured 44 (2013) 1383–1390

A B S T R A C T

Aim: To investigate the state of knowledge on the relationship between physical trauma and mental health in patients admitted to hospital with traumatic physical injury.

Background: Adults who sustain traumatic physical injury can experience a range of mental health problems related to the injury and subsequent changes in physical health and function. However earlyscreening and identification of mental health problems after traumatic physical injury is inconsistent and not routine during the hospital admission process for the physically injured patient.

Methods:

Integrative review methods were used. Data were sourced for the period 1995–2010 fromEMBASE, CINAHL, MEDLINE and PsycINFO and hand searching of key references. Abstracts were screened by 3 researchers against inclusion/exclusion criteria. Forty-one papers met the inclusion criteria. Data were retrieved, appraised for quality, analysed, and synthesised into 5 main categories.

Results: Forty-one primary research papers on the relationship between mental health and traumatic physical injury were reviewed. Studies showed that post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety were frequent sequelae associated with traumatic physical injury. However, these conditions were poorly identified and treated in the acute hospital phase despite their effect on physical health.

Conclusion: There is limited understanding of the experience of traumatic physical injury, particularly in relation to mental health. Greater translation of research findings to practice is needed in order to promote routine screening, early identification and referral to treatment for mental health problems in this patient group.

| Tags : psychiatrie, ptsd

13/09/2013

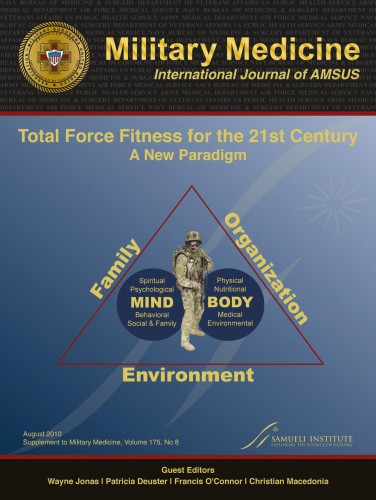

Physical fitness: Une nécessité ?

Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury

21/04/2013

Enjeux de la psychiatrie militaire en opération

| Tags : psychiatrie, ptsd

18/02/2013

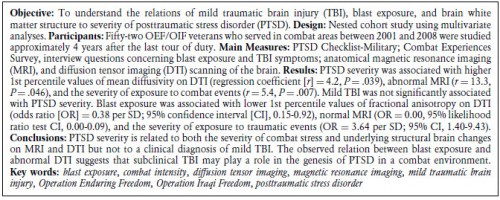

PTSD et Mild TBI: Convergence à l'IRM

The Relation Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Acquired During Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom

| Tags : ptsd, psychiatrie

13/09/2012

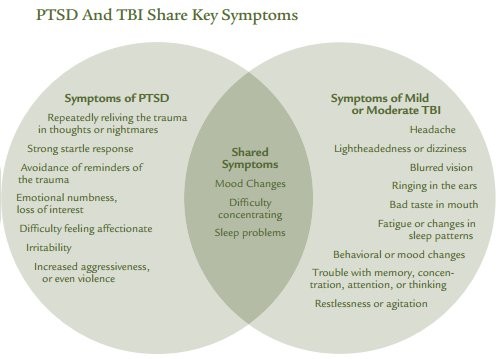

Trauma crânien et psychologique: Le point US

| Tags : ptsd, tbi, psychiatrie

06/07/2012

PTSD an TBI Share Hey Symptoms

Invisible Wounds Psychological and Neurological Injuries. Confront a New Generation of Veterans

| Tags : ptsd

30/04/2012

Recours à la morphine et PTSD

Morphine Use after Combat Injury in Iraq and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Holbrook TL et all. N Engl J Med 2010;362:110-7.

Background

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common adverse mental health outcome among seriously injured civilians and military personnel who are survivors of trauma. Pharmacotherapy in the aftermath of serious physical injury or exposure to traumatic events may be effective for the secondary prevention of PTSD.

Methods

We identified 696 injured U.S. military personnel without serious traumatic brain injury from the Navy–Marine Corps Combat Trauma Registry Expeditionary Medical Encounter Database. Complete data on medications administered were available for all personnel selected. The diagnosis of PTSD was obtained from the Career History Archival Medical and Personnel System and verified in a review of medical records.

Results

Among the 696 patients studied, 243 received a diagnosis of PTSD and 453 did not. The use of morphine during early resuscitation and trauma care was significantly associated with a lower risk of PTSD after injury. Among the patients in whom PTSD developed, 61% received morphine; among those in whom PTSD did not develop, 76% received morphine (odds ratio, 0.47; P<0.001). This association remained significant after adjustment for injury severity, age, mechanism of injury, status with respect to amputation, and selected injury-related clinical factors.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the use of morphine during trauma care may reduce the risk of subsequent development of PTSD after serious injury.

28/04/2012

The injured mind in the UK Armed Forces

The mental health of the UK Armed Forces is a topic much debated by healthcare professionals, politicians and the media.While the current operations in Afghanistan, and the recent conflict in Iraq, are relevant to this debate, much of what is known about the effects of war upon the psyche still derives from the two World Wars. This paper will examine the historical and contemporary evidence about why it is that some Service personnel suffer psychological injuries during their military service and others do not. The paper will also consider some of the strategies that today’s Armed Forces have put in place to mitigate the effects of sending military personnel into danger.

http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/366/1562/2...

| Tags : psychiatrie, ptsd

15/04/2012

Battle mind training: Le système

| Tags : ptsd, psychiatrie

Battle mind training: Bien comprendre

| Tags : ptsd, psychiatrie

Battlemind training: La famille aussi !

| Tags : ptsd, psychiatrie

Batlle mind training: Une fois rentré ?

| Tags : ptsd, psychiatrie