21/11/2025

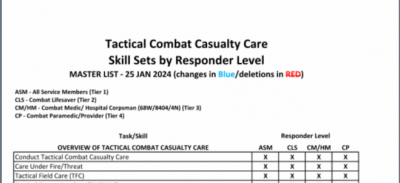

Pratiques gestuelles et niveaux de compétence chez les US

18/01/2020

Absrtacts SOMA

04/11/2019

TCCC: Révision Août 2019

01/05/2019

TCCC: Quoi de réalisé en réalité ?

Prehospital Interventions Performed in Afghanistan Between November 2009 and March 2014.

Lairet J et l Mil Med. 2019 Mar 1;184(Supplement_1):133-137. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy311.

----------------------------

Le bilan des gestes réalisés par les US en afghanistan. Ces chiffres montrent l'importance tant de l'acquisition de pratiques gestuelles que et surtout du maintien des avoirs faire. La gestion des voies aériennes et les gestes de décompression thoracique représentent un enjeu majeur de performance bien plus importan que la maîtrise par quelques uns de techniques d'occlusion endovasculaire préhospitalière.

----------------------------

OBJECTIVE: Care provided to a casualty in the prehospital combat setting can influence subsequent medical interactions and impact patient outcomes; therefore, we aimed to describe the incidence of specific prehospital interventions (lifesaving interventions (LSIs)) performed during the resuscitation and transport of combat casualties.

METHODS: We performed a prospective observational, IRB approved study between November 2009 and March 2014. Casualties were enrolled as they were cared for at nine U.S. military medical facilities in Afghanistan. Data were collected using a standardized collection form. Determination if a prehospital intervention was performed correctly, performed incorrectly, or was necessary but was not performed (missed LSIs) was made by the receiving facility's medical provider.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred and six patients met inclusion criteria. The mean age was 25 years and 98% were male. The most common mechanism of injury was explosion 57%. There were 236 airway interventions attempted, 183 chest procedures, 1,673 hemorrhage control, 1,698 vascular access, and 1,066 hypothermia preventions implemented.

Incorrectly Performed Interventions Comparison of First 1,003 Patients to Second 1,103 Patients

| Overall Data | Interima (n = 1,003) | Post-Interim (1,103) | p-Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airway Interventions | 8.9% | 8.6% | 9.0% | 0.9165 |

| Chest Procedures | 5.5% | 6.7% | 5.2% | 0.6726 |

| Vascular Access | 4.1% | 8.0% | 2.9% | <0.0001 |

| Hypothermia Prevention | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.6860 |

| Hemorrhage Control | 2.1% | 2.2% | 2% | 0.8643 |

| Missed LSIs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Missed LSIs | Total Number of Interventions + Missed Opportunities | Percentage of Missed LSIs | |

| Airway interventions | 56 | 292 | 19.2 |

| Chest procedures | 24 | 207 | 11.6 |

| Vascular access | 160 | 1,858 | 8.6 |

| Hypothermia prevention | 63 | 1,129 | 5.6 |

| Hemorrhage control | 57 | 1,730 | 3.3 |

There were 142 incorrectly performed interventions and 360 were missed.

CONCLUSIONS: In our study, the most commonly performed prehospital LSI in a combat setting were for vascular access and hemorrhage control. The most common incorrectly performed and missed interventions were airway interventions and chest procedures respectively.

16/04/2019

TCCC: Un écosystème spécifique

Un regard sur l'émergence des nouvelles modalités de prise en charge des blessés de guerre avec pour point d'orgue l'innovation conduite et la construction d'un écosystème complet autour de la prise en charge du blessé de guerre. Une démarche à comprendre et à bien méditer.

Clic sur l'image pour accéder au document

09/12/2018

TCCC Update May 2018

10/09/2018

Settings standard for CCC

08/09/2018

Le TCCC dans la vraie vie

Survey of Casualty Evacuation Missions Conducted by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment During the Afghanistan Conflict.

BACKGROUND:

Historically, documentation of prehospital combat casualty care has been relatively nonexistent. Without documentation, performance improvement of prehospital care and evacuation through data collection, consolidation, and scientific analyses cannot be adequately accomplished. During recent conflicts, prehospital documentation has received increased attention for point-of-injury care as well as for care provided en route on medical evacuation platforms. However, documentation on casualty evacuation (CASEVAC) platforms is still lacking. Thus, a CASEVAC dataset was developed and maintained by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR), a nonmedical, rotary-wing aviation unit, to evaluate and review CASEVAC missions conducted by their organization.

METHODS:

A retrospective review and descriptive analysis were performed on data from all documented CASEVAC missions conducted in Afghanistan by the 160th SOAR from January 2008 to May 2015. Documentation of care was originally performed in a narrative after-action review (AAR) format. Unclassified, nonpersonally identifiable data were extracted and transferred from these AARs into a database for detailed analysis. Data points included demographics, flight time, provider number and type, injury and outcome details, and medical interventions provided by ground forces and CASEVAC personnel.

RESULTS:

There were 227 patients transported during 129 CASEVAC missions conducted by the 160th SOAR. Three patients had unavailable data, four had unknown injuries or illnesses, and eight were military working dogs. Remaining were 207 trauma casualties (96%) and five medical patients (2%). The mean and median times of flight from the injury scene to hospital arrival were less than 20 minutes. Of trauma casualties, most were male US and coalition forces (n = 178; 86%). From this population, injuries to the extremities (n = 139; 67%) were seen most commonly. The primary mechanisms of injury were gunshot wound (n = 89; 43%) and blast injury (n = 82; 40%). The survival rate was 85% (n = 176) for those who incurred trauma. Of those who did not survive, most died before reaching surgical care (26 of 31; 84%).

CONCLUSION:

Performance improvement efforts directed toward prehospital combat casualty care can ameliorate survival on the battlefield. Because documentation of care is essential for conducting performance improvement, medical and nonmedical units must dedicate time and efforts accordingly. Capturing and analyzing data from combat missions can help refine tactics, techniques, and procedures and more accurately define wartime personnel, training, and equipment requirements. This study is an example of how performance improvement can be initiated by a nonmedical unit conducting CASEVAC missions.

14/10/2017

TCCC Quick Reference Guide

| Tags : tccc

08/03/2017

TCCC Mise à jour 2017

| Tags : tccc

05/03/2017

Prolonged field care: Un retex

| Tags : prolonged field care

13/11/2015

TCCC: Point 2015

| Tags : tccc

15/07/2015

Bilan US Afghanistan

Clic sur l'image pour accéder au document complet

Le résumé:

Introduction

The U.S. has achieved unprecedented survival rates, as high as 98%, for casualties arriving alive to the combat hospital. Our military medical personnel are rightly proud of this achievement. Commanders and service members are confident that if wounded and moved to a Role II or III medical facility, their care will be the best in the world. Combat casualty care however, begins at the point of injury and continues through evacuation to those facilities. With up to 25% of deaths on the battlefield being potentially preventable, the pre-hospital environment is the next frontier for making significant further improvements in battlefield trauma care. Strict adherence to the evidence-based Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Guidelines has been proven to reduce morbidity and mortality on the battlefield. However, full implementation across the entire force and commitment from both line and medical leadership continue to face ongoing challenges. This report on pre-hospital trauma in the Combined Joint Operations Area – Afghanistan (CJOA-A) is a follow-on to the one previously conducted in November 2012 and published in January 2013. Both assessments were conducted by the US Central Command (USCENTCOM) Joint Theater Trauma System (JTTS). Observations for this report were collected from December 2013 to January 2014 and were obtained directly from deployed prehospital providers, medical leaders, and combatant leaders. Significant progress has been made between these two reports with the establishment of a Pre-Hospital Care Division within the JTTS; development of a pre-hospital trauma registry and weekly pre-hospital trauma conferences; and CJOA-A theater guidance and enforcement of pre-hospital documentation. Specific pre-hospital trauma care achievements include expansion of transfusion capabilities forward to the point of injury, junctional tourniquets, and universal approval of tranexamic acid. CHANGING OLD PARADIGMS “Treat for shock, but do not waste any time doing it.” Fleet Marine Forces Manual “A tourniquet is a last resort for life-threatening Injuries. Tourniquets cut off blood flow to and from the extremity and are likely to cause permanent damage to vessels, nerves, and muscles.” AMEDDC&S Pamphlet No. 350-10 Saving Lives on the Battlefield (Part II) - One Year Later Unclassified 3 Unclassified

Observations & Discussion

TCCC Guidelines are widely, though not universally, accepted as Authoritative “best practices” for pre-hospital trauma care; however, they are not Directive policy. The high degree of variance amongst deployed unit medical personnel, both in terms of clinical training and operational experience, results in inconsistent application and enforcement of TCCC compliance across the force. Since our line commanders are dependent upon their unit medical personnel to inform their understanding, appreciation, and prioritization of medical support requirements, their TCCC commitment and command emphasis understandably varies as well. In the face of near-term resource constraints, without doctrinal and policy endorsement, the Services will continue to struggle to adequately and fully Organize, Train, and Equip to meet TCCC Guidelines as the standard for pre-hospital care. A previous memorandum and recommendation by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs to train all combatants and deployed medical personnel in TCCC remains incompletely implemented across the DoD. In contrast, US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) and US Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) have codified TCCC compliance as policy and reduced pre-hospital case fatality rates. We must continue to embrace and explore emerging capabilities to deliver far-forward resuscitative care. Those capabilities that are both responsive and adaptive to the dynamic tactical landscape hold the greatest intrinsic value for our line commanders and their personnel. We must also ensure that our supporting Organize, Train, and Equip functions have the agility to keep pace with these evolving standards of care. We must increase the investment in our medical personnel to develop and retain true expertise in pre-hospital trauma care delivery and oversight. These must become core competencies in the unique domain of operational medical support and we must embrace new medical training paradigms that advance these skills. Finally, officer professional development for both line and medical leaders must emphasize the shared responsibilities for developing and enforcing robust unit commitment to lifesaving pre-hospital trauma care principles.

Findings

1.The lack of standardized TCCC capability may represent a causal factor for the increased killed in action, case fatality rate, and preventable deaths seen in conventional forces when compared to special operations forces. 2. Absent a validated joint requirement which is captured doctrinally, the prevailing resourceconstrained environment will challenge Services to fully Organize, Train, and Equip to TCCC standards. Saving Lives on the Battlefield (Part II) - One Year Later Unclassified 4 Unclassified 3. There is no evidence that the DoD or CJOA-A has policies or procedures in place to validate or enforce pre-hospital care within an organization. Service-specific doctrine requiring Unit Surgeons to each establish a standard of care, allows for variant, non-standard delivery of battlefield trauma care across the force. Furthermore, even within a single command, rotation of Unit Surgeons introduces and magnifies discontinuity of unit trauma care standards. 4. The requirements to perform and support pre-hospital TCCC could be standardized across Services (universally or at the Combatant Command level) with the specific means to achieve these Train & Equip standards left up to the respective Services. 5. As with elements of pre-hospital care, organization structures are highly variant with a number of at-risk forces not having adequately manned/trained/equipped medical support. 6. Units with a tactical evacuation mission requirement should be task organized to be able to provide advanced enroute resuscitative care from the point of injury. 7. Robust training platforms exist for pre-hospital trauma care, though not all course training syllabi keep pace with current best practices. Sufficient information technologies exist to rapidly and widely disperse new TCCC Guidelines as they become immediately available. 8. Unit equipment sets and supporting medical logistics systems have not kept pace with evolving pre-hospital care TCCC guidelines. Out-dated items remain within the supply chain and newly required items have not yet been incorporated into standard configurations. 9. In the absence of a widely mandated policy that establishes TCCC Guidelines as the standard for pre-hospital battlefield care, and accountability for deviations from this standard, the degree of penetrance and acceptance of TCCC Guidelines will remain episodic and dependent upon individual (Surgeon and commander) commitment. 10. Neither line nor operational medical leaders are optimally prepared to recognize the importance of a robust, pre-hospital care system, or equipped with the requisite knowledge, skills, or experience to build or sustain such a system within their unit.

New Recommendations

1. DoD establishes TCCC Guidelines as the DoD standard of care for pre-hospital care. 2. DoD conducts a DOTMLPF-P assessment across Services to assess and implement TCCC Guideline capability. 3. DoD systematically review and correct all pre-hospital care doctrine across the spectrum to accurately represent TCCC Guidelines with the doctrine specifically stating “in accordance with Saving Lives on the Battlefield (Part II) - One Year Later Unclassified 5 Unclassified the current TCCC Guidelines published by the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care” to ensure that the doctrine remains current. 4. Services immediately implement an aggressive transition initiative to update all relevant medical equipment sets and medical logistic policies to ensure units have TCCC Guideline specified medical materials. 5. DoD establishes a Battlefield Pre-Hospital Trauma Care Program Proponent (or equivalent structure) in the DHA. 6. DoD develop and mandate a TCCC Accreditation, Certification, and Recertification program like Basic Life Support, Advanced Trauma Life Support, and Advanced Cardiac Life Support for all military personnel with a requirement for biannual re-certification and as based on level of ability and position (e.g. Non-Medical First Responder, Non-Medical Leader, Medical Provider, Medical Leader). 7. Services require and track TCCC certification for all pre-hospital medical personnel and integrate tracking into combatant Unit Status Reports. 8. Services incorporate TCCC Champion training into all basic and advanced officer and noncommissioned officer professional military development courses. 9. Services incorporate and mandate casualty management and hands on practical exercises into all professional military development courses. 10. DoD updates the Joint Capability Requirement for Tactical Enroute Care to include the ability to provide advanced resuscitative care from the point of injury. 11. As military physicians are ultimately responsible for assuming the role of EMS Director for pre-hospital services if assigned to a combatant unit, the military Services should study and develop career, educational and assignment tracks for operational medical corps officers which includes emphasis upon pre-hospital care delivery.

Conclusion

History teaches that the lessons we have learned regarding combat casualty care may be lost if we fail to attend to them in the coming years. Even in a resource-constrained future, the MHS has the necessary raw materials of personnel, organization, and experience to retain and refine our current best practices. With continued efforts aimed at 1) formalizing TCCC Guideline compliance across the force; 2) embracing evidence-based methods to continually improve upon these Guidelines; and 3) selecting, developing and retaining operational medical personnel dedicated to pre-hospital trauma care, the MHS will ensure an organizational culture that fully embraces pre-hospital combat casualty care as a core competency.

| Tags : tccc

10/07/2015

Le point sur la réalité du TCCC US

04/09/2014

Remplissage vasculaire: Evolution majeure du TCCC

L'emploi préhospitalier de la transfusion de globules rouges et de plasma était évoqué de manière anecdotique. Une évolution importante survient dans la procédure américaine du TCCC (1, 2). Cette pratique est en passe de devenir une recommandation protocolée de théâtre pour les blessés en état de choc (Pas de pouls radial et conscience altérée el l'absence de traumatisme crânien) hémorragique avec notons le recours au Plyo du CTSA.

" Tactical Field Care and TACEVAC Care

7. Fluid resuscitation

a. The resuscitation fluids of choice for casualties in hemorrhagic shock, listed from most to least preferred, are: whole blood*; plasma, RBCs and platelets in 1:1:1 ratio*; plasma and RBCs in 1:1 ratio; plasma or RBCs alone; Hextend; and crystalloid (Lactated Ringers or Plasma-Lyte A).

b. Assess for hemorrhagic shock (altered mental status in the absence of brain injury and/or weak or absent radial pulse).

1. If not in shock:

- No IV fluids are immediately necessary.

- Fluids by mouth are permissible if the casualty is conscious and can swallow.

2. If in shock and blood products are available under an approved command or theater blood product administration protocol:

- Resuscitate with whole blood*, or, if not available

- Plasma, RBCs and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio*, or, if not available

- Plasma and RBCs in 1:1 ratio, or, if not available;

- Reconstituted dried plasma, liquid plasma or thawed plasma alone or RBCs alone;

- Reassess the casualty after each unit. Continue resuscitation until a palpable radial pulse, improved mental status or systolic BP of 80-90 mmHg is present.

3. If in shock and blood products are not available under an approved command or theater blood product administration protocol due to tactical or logistical constraints:

- Resuscitate with Hextend, or if not available;

- Lactated Ringers or Plasma-Lyte A;

- Reassess the casualty after each 500 mL IV bolus;

- Continue resuscitation until a palpable radial pulse, improved mental status, or systolic BP of 80-90 mmHg is present.

- Discontinue fluid administration when one or more of the

above end points has been achieved.

4. If a casualty with an altered mental status due to suspected TBI has a weak or absent peripheral pulse, resuscitate as necessary to restore and maintain a normal radial pulse. If BP monitoring is available, maintain a target systolic BP of at least 90 mmHg.

5. Reassess the casualty frequently to check for recurrence of shock. If shock recurs, recheck all external hemorrhage control measures to ensure that they are still effective and repeat the fluid resuscitation as outlined above.

* Neither whole blood nor apheresis platelets as these products are currently collected in theater are FDA-compliant. Consequently, whole blood and 1:1:1 resuscitation using apheresis platelets should be used only if all of the FDA-compliant blood products needed to support 1:1:1 resuscitation are not avalaible

| Tags : choc, coagulopathie, remplissage